Hearing Impacts Brain Function

Hearing Loss impacts Brain Function

Contributed by Lisa Packer

June 18, 2015

When we think of the word “reorganization”, we don’t usually associate it with the brain; but now a new study indicates that is exactly what happens when we start to lose our hearing. The good news is that this new information is shedding new light on the correlation between hearing loss and dementia, and could have long term implications for hearing loss screening and intervention.

The study, done at the University of Colorado’s Department of Speech Language and Hearing Science, looked at how neuroplasticity — how the brain reorganizes itself by forming new neuron connections throughout life — plays into the adaptation of the brain after hearing loss. The study sought to answer two questions: How does the brain adapt to hearing loss and what are the resulting implications?

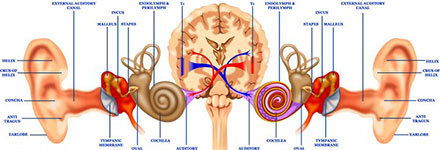

This scan was used by researchers to provide a glimpse behind how our brain absorbs sound.

Anu Sharma/University of Colorado

Neuroplasticity is, in effect, the brain’s ability to change at any age. Conventional wisdom used to view the brain as static and unable to change; scientists now know this is not the case. In the case of hearing loss, the part of the brain devoted to hearing can actually become reorganized, i.e. reassigned to other functions.

The participants in the study were adults and children with varying degrees of hearing loss; some had only mild hearing loss while others were severely hearing impaired or deaf. Using up to 128 sensors attached to the scalp of each subject, the team of researchers used EEG recordings to measure brain activities in response to sound stimulation. By doing this, they were able to understand how the brains of people with different degrees of hearing loss respond differently than those of people with normal hearing.

Perhaps most importantly, the researchers found when hearing loss occurs, areas of the brain devoted to other senses such as vision or touch will actually take over the areas of the brain which normally process hearing. It’s a phenomenon called cross-modal cortical reorganization, which is reflective of the brain’s tendency to compensate for the loss of other senses. Essentially, the brain adapts to a loss by rewiring itself. It is a makeover of sorts, but one that can have a seriously detrimental effect on cognition.

Even early stages of hearing loss can lead to cognitive decline. Healthy hearing and early intervention in the event of any degree hearing loss are essential to maintaining strong cognitive function. As a matter of fact, a recent French study that looked at the result of cochlear implants in the elderly showed that cognitive skills improved as speech comprehension improved.

In those with hearing loss, the compensatory adaptation system significantly reduces the brain’s ability to process sound, which in turn affects a person’s ability to understand speech. And even with mild hearing loss, the hearing areas of the brain become weaker. What happens next is that the areas of the brain that are necessary for higher level thinking compensate for the weaker areas. They step in and essentially take over for hearing, leaving them unavailable to do their primary job.

“The hearing areas of the brain shrink in age-related hearing loss,” said Anu Sharma, PhD, a researcher on the University of Colorado study. “Centers of the brain that are typically used for higher-level decision-making are then activated in just hearing sounds. These compensatory changes increase the overall load on the brains of aging adults. Compensatory brain reorganization secondary to hearing loss may also be a factor in explaining recent reports in the literature that show age-related hearing loss is significantly correlated with dementia.”

Compensatory brain reorganization could explain why age related hearing loss is so strongly correlated with dementia, and why it must be taken seriously. Even in the early stages of hearing loss, the brain begins to reorganize. Knowing this, the solution could be as simple as early hearing loss screening programs for adults. Getting ahead of the decline through early intervention could prevent long term cognitive issues down the road.

The could also have implications for deaf children with cochlear implants. Looking at the brain waves of a child with cochlear implants could indicate the specifics of that child’s cross-modal reorganization and could allowing doctors to tailor a hearing rehabilitation program to the individual child.

The team at the University of Colorado isn’t finished yet; practical applications of the study are next. “Our goal is to develop user-friendly EEG technologies, to allow clinicians to easily ‘image’ the brains of individual patients with hearing loss to determine whether and to what degree their brains have become reorganized,” said Sharma. “In this way, the blueprint of brain reorganization can guide clinical intervention for patients with hearing loss.”

Hearing loss is one of the most common conditions affecting older adults. According to the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD), one out of three people between the ages of 65 and 74 have some degree of hearing loss. The number increases to almost 50 percent for those over 75. However, less than 25 percent of people who need hearing aids actually get them. The average time someone with hearing loss waits to seek treatment is seven years, which is a tremendous period of cognitive decline that is easily preventable.

If you think you may have hearing loss, make an appointment with your local hearing healthcare professional.